- DESCRIPTION

- UTOPIAN INFRASTRUCTURE: THE CAMPESINO BASKETBALL COURT

- ELEMENTS OF THE PROJECT

- TEXTS

- PHOTOGRAPHS

MEXICO PAVILION 18TH INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

EXHIBITION LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

↔

26.[NOV].2023

The basketball court as liminal territory in the work of Kasser Sánchez

Author: Viridiana Martinez Marín

The community basketball court is a contingent space that is not only activated by its use as a sports facility, but by all the possibilities of producing agencies that this site has in a community. The various practices that take place there have to do with the political, affective, festive and economic dynamics of a town, these events are not exclusive, they are one and the other at the same time, a festival or fair that is celebrated in the space of the basketball court is as political as an assembly to make community decisions.

In a state as large as Oaxaca, boundaries divide the land into 570 municipalities, however, this does not mean that the center of each municipality is the meeting point of the towns and neighborhoods that inhabit those demarcations, each town or neighborhood has its own center which is itself associated with the basketball courts that are close to elementary and middle schools. For example, the place where I grew up is part of the municipality of Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán in Oaxaca, however, our center was not the Xoxo municipal agency, but the basketball court near my elementary school, the place where I watched a movie projection for the first time, because a traveling group that showed religious themed movies invited us to their screening on the court, the place where my classmates and I also met to rehearse the dances that we would perform at the festivities on dates such as Independence Day on September 16 or Mother’s day on May 10.

In one of my classes with Dr. José Ángel Quintero Weir, who often spoke of the Wayú people, he told us that each town has its own stories about the origin of the world, which constitute their worldview, that is, the stories that produce the image of the people, and that each one of these populations sees itself as the origin of the world. These are aspects that I find very important when thinking about the various processes and histories that constitute the territory at a local level, even though they are within the demarcation of a municipality or state. In that same class, Dr. Quintero Weir told us that the territory is made up of materially or spiritually significant places and that each town makes their territory from a place because at a certain moment, it constitutes a significant space for the group. This resonates with what happens with the basketball courts in many places in Oaxaca where people meet and generate community practices.

These are the questions raised by the artist Kasser Sánchez, originally from San Baltazar Chichicápam in Oaxaca, in his project Laah nu´ / Laah tu´ which translates to us / you [plural] in the Zapotec language spoken in his town. His work consists of a series of sculptural pieces, graphics, 3D modeling, paintings and drawings, which reflect on the community basketball court as a liminal space where, in addition to game dynamics, various social, political and historical relationships take place, in which the members of a community coexist and participate.

Liminality is a concept used to designate a transitory space (physical or mental), an intermediate phase between community rites that celebrate change, the necessary mutation for the continuity of a community. Sánchez finds the liminal in the court by observing that, despite being a space for playing sports, the various practices within it simultaneously make it into other spaces, without ever ceasing to be what it is in its essence. That is to say, for Sánchez the spaces of the basketball court can become a political forum, an assembly for urgent issues, while they remain a space for playing sports, marked by the architecture of the court, by the visual references of sports brands, by the boards, the lines that mark the field, the baskets and their nets. These aspects trigger a series of images that Kasser Sánchez materializes in his work.

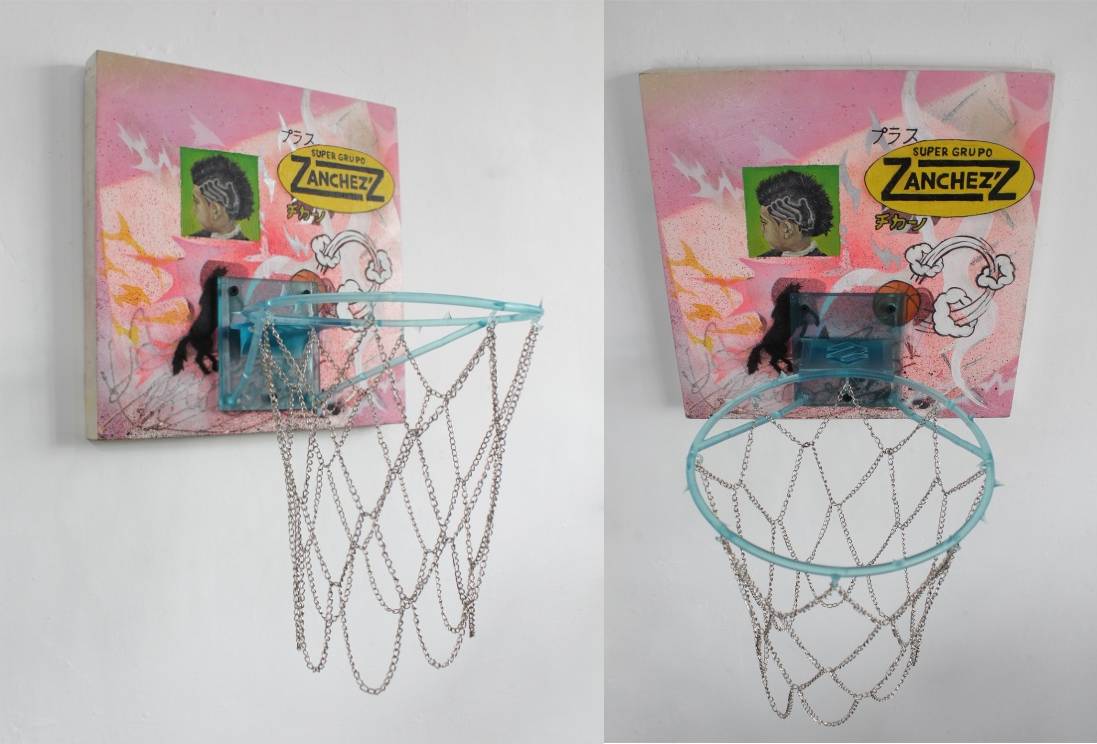

For example, in the piece Convergencia S-Z, Sánchez uses a wooden-framed canvas as a basketball backboard, a 3D-printed sculpture thorned hoop, and a net made of metal chains. The canvas displays a collage painting with images such as a cartoon basketball, a boy with a crew cut, and the sign of a band that was popular in his town during the 1980s.

Oil, spray paint, and 3D resin hoop with chain on stretcher. 30 x 43 x 30 cm. 2022

Each of the graphic and sculptural elements that make up Convergencia S-Z are linked to the territory from which they arise, and they evoke negotiations about public space, intergenerational dynamics and community encounters. The thorns in the hoop, for example, recall elements that represent two converging spaces in various towns in Oaxaca that are given new meaning through their social activations: one is the basketball court and the other is the atrium of the Catholic church. The uses of both spaces are not limited to their structured function, but rather, they are containers of affective and thus political flows.

In another of the pieces that bears the name of the project, Laah nu ́/ Laah tu ́ . Sánchez makes a sculpture from the material and contextual resignification of a tortilla metal press, which he intervenes using sheet metal and concrete and modified its base to form a basketball court with two boards made of mirrors. In a basketball game, the teams are usually described as locals (us) and the visitors (you), words in Zapotec inscribed respectively on each board. With the use of mirrors, Sánchez reflects on the territory, on the associations that mark the collective ownership, commitment and care of the land and how this must be generated from the link with other neighboring territories. On this piece and in the reflection of its mirrors, one can think that in the recognition of the other, we know ourselves, a connection and empathy necessary to move from a society based on subjectivity to one based on collectivity.

![Laah nu ́/ Laah tu ́ (us/you [plural])](/static/img/kasser-sanchez-2.jpg)

Metal, sheet metal, concrete, mirrors, vinyl cutout, and paint. 100 x 50 x 33 cm. 2018

Zapotec from San Baltazar Chichicápam, Ocotlán, Oaxaca

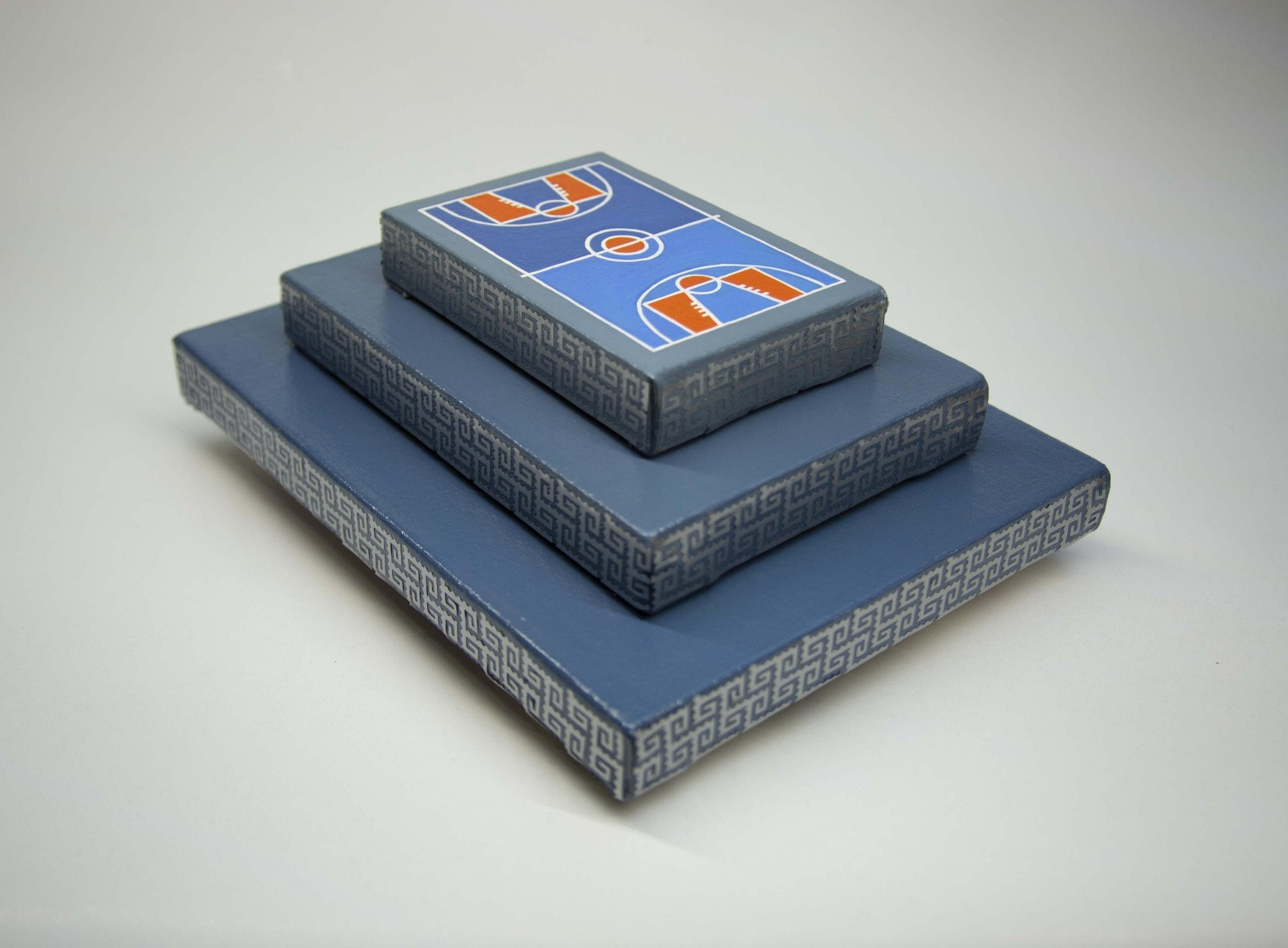

In another piece titled Cancha comunitaria (Community Court), Kasser uses three wooden-framed canvas of different sizes that are superimposed one on top of the other to compose a sculpture. It is a pyramid in which the canvases are used as stairways to reach the top, a composition that resonates with the architectural structure of Monte Albán, a Zapotec pre-Hispanic city that means “Sacred Mountain”. The canvases, like stairways, are intervened with silver fretwork made with cut vinyl on a background of blue paint. The use of colors might be an allusion to the meaning of Binnizá (binni, people; zá, cloud: people who come from the clouds), a word from the Zapotec language of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. In addition to these associations, the top of the pyramid, where Sánchez paints a basketball court, recalls the relationship between the multiple uses of the sacred territories in Monte Albán, political, religious, aesthetic and for sports, since in Monte Albán ballgame courts have been identified as a ritual space where political and religious issues converge, as in Sánchez’s proposal to think of the community basketball court as a liminal space, a ritual, political and sports contingency of intergenerational negotiations.

![Cancha comunitaria (Laah nu ́/ Laah tu ́) II (us/you [plural])](/static/img/kasser-sanchez-6.jpg)

Metal, sheet metal, concrete, mirrors, vinyl cutout, paint, and LED lights. 120 x 50 x 30 cm. 2021

Zapotec from San Baltazar Chichicápam, Ocotlán, Oaxaca.

Similarly to these examples, the other pieces that make up the Laah nu´/ Laah tu´ project explore and experiment around the representations of the basketball court, taking up elements of sports graphics, Zapotec inscriptions, visual references of the images that circulate in the artist’s town and pop culture images from the generation to which the artist belongs, to generate pieces that talk about the multiple practices and relationships that take place on the community court.

Dr. Quintero Weir reminds us that “There is no memory without territory” This means that any corporality constitutes its memory from the links it has established with the territory. In this sense, Sánchez works with thevisual memories from when he was a child and walked through his town, in which he saw signs announcing the next dance to be held on the court, the memories of going with his parents to the courts where political assemblies were organized to discuss the town’s material problems and later returning to his house to watch the cartoons that were broadcast on television. All these memories are contained in a dynamic and dialogical way in the material and graphic gestures of his pieces.

Sánchez’s pieces remind us that there is no single way of doing political practice, that each town has its own ways of generating society, that is, of establishing associations, and that these dynamics are essential for communal life. For San Baltazar Chichicápam, the where Sánchez is from, as in many other territories in Oaxaca, basketball courts are containers of active memories, spaces for political negotiation, and the stage for activities as diverse as a dance, a party, a film screening, or an assembly.

Acrylic painting intervention and installation of artwork and object in a room. 6.5 x 4.35 m. 2017

Acrylic painting on canvas, vinyl cutout, lacquer, and resin. Modular piece. 21.7 x 8.7 x 28.7 cm. 2020

Acrylic painting on concrete, wooden frame with vinyl cutout and resin. 26 x 2.5 x 29 cm. 2020

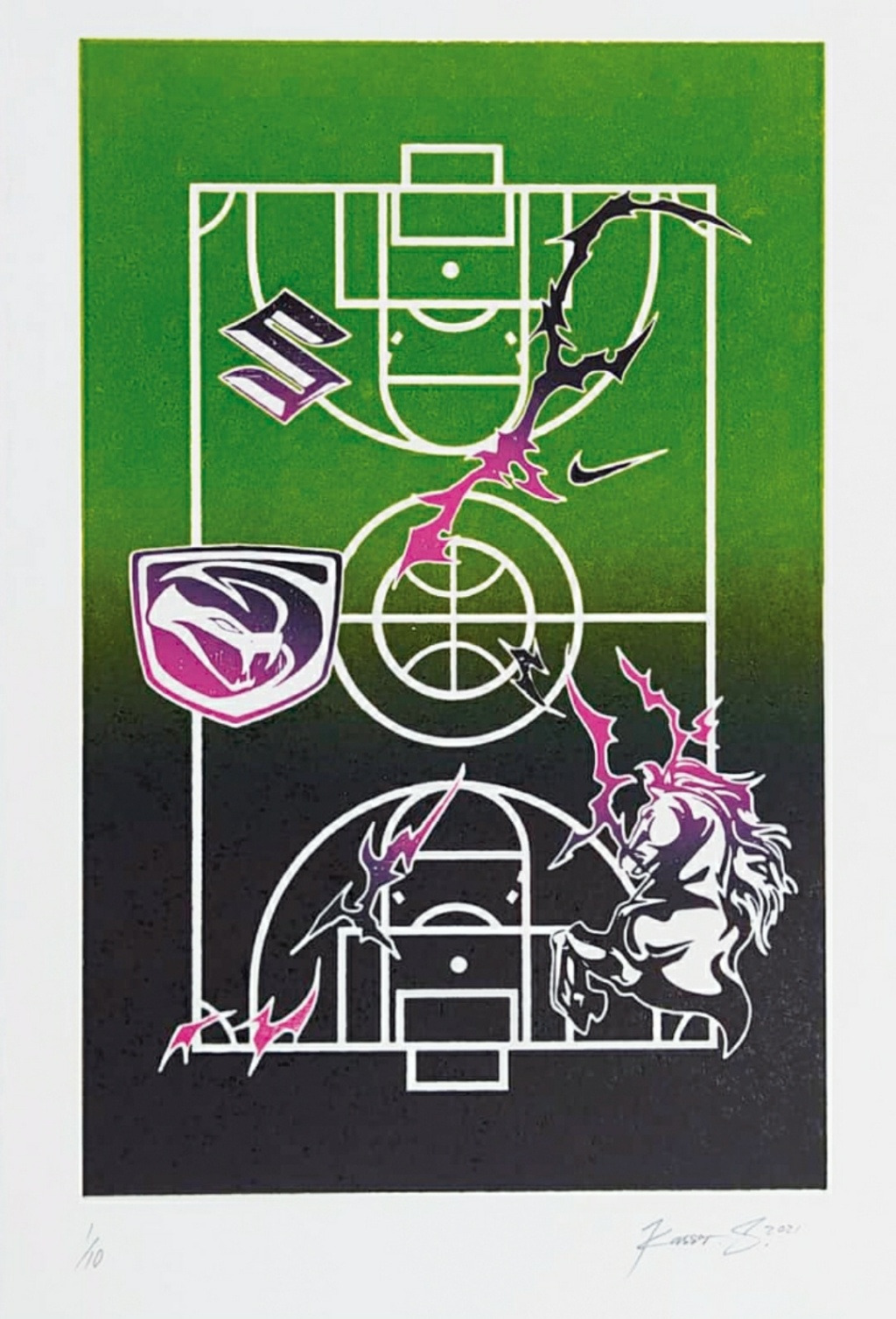

Laser-printed woodcut on cotton paper. 1/10 35 x 50 cm. 2021

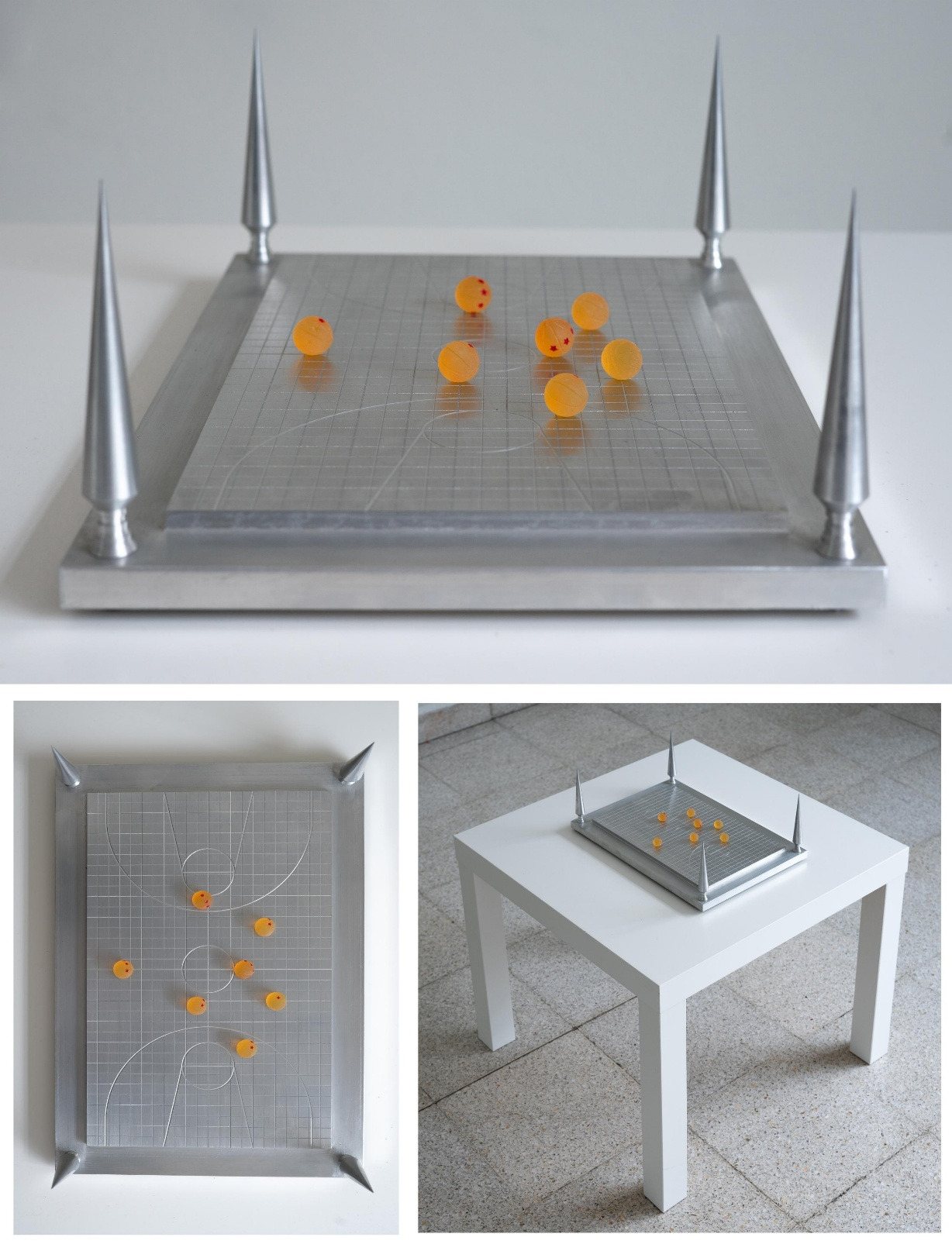

CNC engraved and milled aluminum plate with 3D resin balls and enamel paint. 24 x 35 x 12 cm. 2022

Oil, spray paint, and 3D resin hoop with chain on stretcher. 30 x 43 x 30 cm. 2023