- DESCRIPTION

- UTOPIAN INFRASTRUCTURE: THE CAMPESINO BASKETBALL COURT

- ELEMENTS OF THE PROJECT

- TEXTS

- PHOTOGRAPHS

MEXICO PAVILION 18TH INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

EXHIBITION LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

↔

26.[NOV].2023

The Life and Times of a Basketball Court

Author: Delmar Penka

The Struggle is like a circle,

You can begin at any point,

But it never ends.

– Subcomandante Marcos

I ¶

Time is movement. Nothing exists without it. It is a basic principle of life expressed in everything we see, think and feel. The movement of the clouds on a rainy day, the autumn breezes that move the bark of the trees and the last leaves and the sprouting of the pear trees after their hibernation. It’s manifest in the days spent working in the milpa, as the sun advances to its highest point at midday and then descends so that the afternoon and night can show themselves in the sky. Time is in corn, in the earth, in fruit trees, in the harvest. You feel it in the trails you walk to get from one point to another; perceive it in feet, in hands, in sweat, in eyes; in the daily labor that accompanies us from the beginning of our days until the end.

Time is constant movement, its spiral rhythm a cycle that comes and goes but never turns backward. That is how time is conceived in our communities, in country life, where the days go by at the pace of a snail, advancing slowly but towards a fixed horizon being built by walking. Time becomes communal when people gather to share space and movement, when they celebrate a festival, watch a film or erect a structure that requires everyone’s strength, creativity and hard work.

Building a basketball court for a collective end is the result of shared time. You can neither think of nor erect one from a posture of individualism. This is among the first values we’re taught as children in order to live and learn as a community: collaboration. Time, then, means to join in and participate in activities that will benefit everyone. A basketball court is just that: a space where generation after generation can meet.

On the court, anything is possible, whatever the imagination can built takes place. It’s where the utopia of organization becomes a reality.

II ¶

The year was 1945. My great-grandfather Nicolás, with the support of his companions, had finally managed to acquire the lands that would become the community of Ach’lum in Tenejapa (a municipality in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas). That audacious accomplishment was the result of a long process and arduous work, of long hikes from the place where the community would be built to the state capital. That trip used to take five days on foot with rests each night in the halls of some kind person’s home, offered to the walkers as the night caught up with them. Obtaining recognition of their rights as landholders was a shared victory.

Once they’d formalized the distribution of land between the ejidatarios (the shareholders of the communally owned territory), the families that had formed part of the petition, and who came from different villages, moved to Ach’lum. Having settled in their new community, the next step was to decide where they would place the school and the basketball court that they’d imagined but did not yet exist. They decided to place them in the center of the community. The families built their houses around that open space, between the crags that dotted the terrain.

Five years later, the same people who had managed the acquisition of the land were chosen to solicit the construction of a school. The community believed in them; a new journey began. As before, they experienced exhaustion in their feet and in their breathing, but they shared the hope of a school for the village children. With Spanish barely settled on their tongues, they arrived at the Government Palace and left their request, written by hand by a young man who had taken classes at the National Indigenous Institute in San Cristóbal de Las Casas. He was the only person who knew how to write; people remember him as joven Antonio—the youth, Antonio—who would eventually become the village’s first teacher. It took a year for the project to be approved. Everyone was overjoyed because, with its classrooms and its basketball court, the community would finally be complete.

When the funds were released, the men of the community organized themselves to build the school. They spent their mornings working in the milpa and in the afternoons they got together to move ahead with the construction. It was a long, slow process, based on the time available of those who worked. It was a splendid expression of the philosophy of komon a’tel, or collective work.

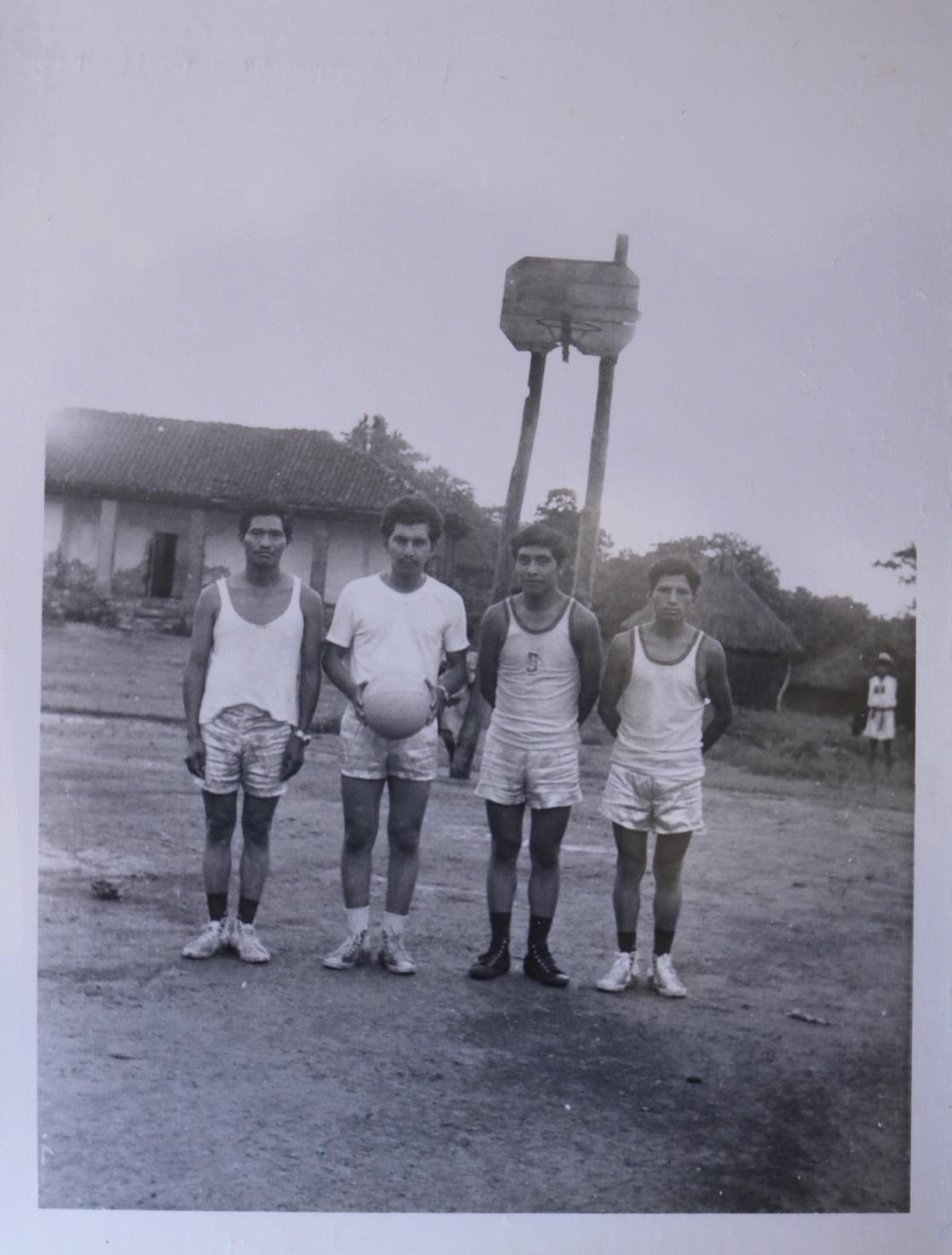

After eight months, they finished construction on the school. To one side was the basketball court. It was very simple: asphalt, a wooden post and backboard, a hoop made from a length of hose. The ground wasn’t completely flat, but that didn’t matter: people got used to playing around the dimples in the surface.

The people organized a party to inaugurate the new project. The spouses of the committee members gathered on the court, collected wood, lit a fire and prepared the chicken soup, made from the hens contributed by each family. The elderly prayed, offered their words and gave food to the earth; they asked permission and entreated the sacred beings that no one should injure themselves on the court and that every child should find at school a place where they might grow and be happy. After the prayer of the elders, the people ate. This is how we dedicated the project that, to this day, lives on in the community of Ach’lum.

The basketball court is a direct result of the countless hours that every member of the community gave, men and women, without exception—it doesn’t matter what materials they offered, but rather the time they committed. What matters are the dreams, the laughter, the exhaustion and the hopes shared by those who lent their strength to the effort. And prior to that, the willpower of those who managed to obtain the space and the resources to make it possible—the school and the basketball court, together, are the sum of all that dedication, hence the value we place in caring for them and in the story behind them.

My great-grandfather Nicolás died in the summer of 2015. Our family and the entire community gathered. We cried together. The last of Nicolás’s generation shared their happy recollections of him, his vitality and youthfulness and how he’d gathered in the afternoons with the other men to play basketball. He did this for 50 years until his body had aged and he could only come to the court to watch. He played on this basketball court and so did my grandfather, Domingo; my father Alonso and I do, too—we four generations have been happy in the this same place and perhaps my descendants and the ones who follow them will be, too.

III ¶

To build a basketball court is to erect a common space for the community. It becomes that community’s center and its heart. It’s difficult to imagine a village or a community without a basketball court; they’ve become part of the way people inhabit space, a part of the environment that people pass through every day. For as long as I’ve been travelling between native communities in Chiapas and Oaxaca, I’ve always found basketball courts. They come in different shapes and sizes and have transcended their original aims as spaces for play, opening the way for many other communal purports.

It’s quite possible that it never crossed the mind of basketball’s inventor, James Naismith, that, in some faraway mountain town in Mexico, a basketball court would be used by merchants setting up their fruit and vegetable stalls on market days, would become a place where one can feel and perceive different colors and aromas and sounds as people murmur their hellos to friends and acquaintances.

It’s the presence of people that fills these basketball courts with life, people who use these spaces to play, to sing, to sell, to chat, to exchange; to look and to listen to everything that takes place within them. The heartbeats of all those people coalesce in that space. That’s how they take on an emotional significance that can be felt in the body, the heart and the soul of every person.

Every once in a while, people get together to clean the court. They remove dust and spiderwebs, they wash and they paint—if they have paint on hand. Usually this happens in preparation for community festivals or New Year celebrations. To keep the court in good condition is a way of showing affection for it because it is not an inert object but rather an integral part of the community and its families. The basketball court feels, too.

IV ¶

Some time ago, in my desire to understand the meanings ascribed to the basketball court by members of the community, I decided to ask every person I encountered: “What does the basketball court mean to you?” The answers were diverse and revealed everyone’s profound feelings for the place of the game. Some of the answers included: “it’s where I have fun,” “it’s where I practice and train,” “it’s where I dry my beans,” “it’s where I played as a kid,” “it’s where I go when I feel bored,” “it’s the place where I am happy,” “it’s where we get together for meetings or games,” “it’s where the boys and girls play basketball,” “it’s where the straw bull dances during Carnival.”

_Have you ever asked yourself how the basketball court came to be in your village? _Even presenting that question can set people on a journey to seek out their own court’s origins. No basketball court exists just because. There is always something that raised it up, but that something is always unknown. I invite you, when you return home to your neighborhood or to your community, to ask your grandfathers and grandmothers, your neighbor, your aunt. I am certain they’ll be able to tell you the story of the basketball court.

V ¶

A basketball court is:

a place where we make our hearts happy

where the collective voice is heard

every time there’s an assembly.

The place where my mother

played in her infancy

and danced on the day of her graduation.

It’s the space for encounters,

where people dry their recently harvested coffee.

The abode of my joys,

the refuge where sadness is diluted.

VI ¶

The basketball court has been present at various points in my life. I’ve come to think that, without it, the most luminous moments that I can remember would never have been possible. I can’t imagine myself without the court. This shared thought-feeling belongs to everyone who holds those days of delight in their memory. The Tzeltal _people call their basketball courts _yawil tajinabal—that is, “the place of play.” The name itself suggests the metaphor of its existence and the feeling it provokes.

On the basketball court, different time frames and experiences layer together as people convene. My father used to rest there while others played their game. My grandmother would hull beans at the sidelines while she watched the young people and those who were finishing up their daily chores would assemble to watch while drinking a bit of pozol (a beverage made from ground corn and cacao). The day, meanwhile, continued on its course until the night made itself present, at which point everyone would go. In that one place, you could feel time in all its particularities.

I find this idea intriguing when I think of my own experiences, the circumstances that evoke them, and the things the basketball court taught me. Among those experiences was one that took place when I was in primary school. Some teachers made a planetarium in the middle of the basketball court. It was a big, white sphere. None of my friends had any idea what this thing could be—it seemed to us completely strange. Once it was installed, we went inside in groups. At the beginning we were nervous, but we wanted to find out what was inside. Everything was dark, then a dim light began to illuminate the space and, in a few seconds, it had sketched out the night. There were tons of stars, as many as we see in the sky.

One of the teachers revealed to us their intention in putting together the planetarium: to learn the names of the planets and the universe. My friends were as amazed as I was. We listened with close attention, the first time that we’d all kept quiet. Time seemed suspended. It had a different rhythm. Although we remained seated, we felt as though we were moving with the planets. After an hour, the explanation ended and we had to leave the planetarium. Nobody kept their fascination to themselves; it was the subject of conversation for the rest of the week. Then one Monday, when we arrived at school, the planetarium was gone. We felt a certain nostalgia but also joy at having learned about outer space thanks to an object set down in the basketball court.

The second experience took place years later. My father had asked me to accompany him to the monthly village assembly. The ejidatarios had gathered on the court. Together, they planned to decide on a date for the annual cleaning of the rivers and the springs, among other things. The meeting began at six in the evening. The committees presented their proposals and, before making any decisions, everyone had a chance to participate. When one group finished speaking, the next began, one after another. Everyone shared their opinion.

I listened as each person spoke and noticed that everyone else kept quiet. They paid such close attention. It was important to listen in order to make decisions. My father had invited me not because he wanted my company but rather because I would soon reach my age of majority and begin participating myself and I would need to know the rhythms and the rules of the assembly. No one says it explicitly, but all of the young people in my community learn to participate.

Night had fallen and it was time to reach a consensus. The ejidatarios agreed on a date and a time to begin the communal work. Before everyone departed for their houses, I reflected on the time and the place of the assembly. The court had become a space where the collective voice was possible, where the will of the community was validated. When you think about the fact that the same practice is carried out in every town, it becomes clear that this wasn’t circumstantial. The court, then, allows us to become brothers.

A few days ago I found out about something that had happened in the past, when a basketball court became a guidepost for finding and rebuilding a buried town. It was the end of March 1982 when the Chichonal Volcano, known among the Zoque people as Pyogba chu’we (the woman who burns), erupted. Several nearby towns were buried in rubble, fire and ash. Forty years later, the survivors of the community of Guayabal decided to look for the remains of those who hadn’t escaped. They searched for a marker in the countryside. As luck would have it, they could detect the tip of a basketball post just visible above the surface of the earth. That’s how they discovered their yearned for sign.

The people began the excavation, which took weeks and a great deal of effort. Little by little, the remains of the village made themselves seen. The façade of the church appeared, the house of a neighbor, too. Thus, slowly, everything began to take shape, including the basketball court. There were no hoops or backboards, but the posts were there. Everyone gathered in its center to commemorate what had taken place. The vestiges of the court became, after all that time, a place of memory. The practice of gathering there did not change, despite the fact that the court had spent four decades underground. In time, the village and the basketball court had been reborn.

VII ¶

A ball spins

in the middle of the court,

rolls like time,

like the world,

like life.

–

Translation: Michael Snyder

Proofreading: Jaime Soler Frost